Preparation for Yoga - I. K. Taimni

I. K. Taimni

Originally published in The Theosophist, February 1967

The discussion about the nature of Samadhi in the first chapter of the Yoga-Sutras of Patanjali and the subtle mental processes which are involved in it might well give the impression that the technique of Yoga is not meant for the ordinary man and he can at best make only a theoretical study of the subject and must postpone its practical application to his own life for some future incarnation when the conditions are more favourable and his mental and spiritual faculties have developed more fully. This impression, though natural, is based upon a misconception.

Those who formulated the philosophy of Yoga and devised its elaborate technique were not so ignorant of the weaknesses of human nature and the limitations and illusions under which an ordinary man lives. They could not point out the necessity and urgency of man’s freeing himself from these limitations, and then place before him a method of achieving this object which seemed to be beyond his capacity.

They knew the difficulties which were involved, but they also knew that these difficulties could be overcome by adopting a graduated course of training which is scientific and in accordance with the laws of human growth and evolution. Even in achieving any worthwhile worldly object a person has to proceed systematically and be prepared for a prolonged and strenuous effort.

If he wants to become a great mathematician he begins with the four rules of arithmetic and gradually works his way up from one stage to another until he masters the science. He does not start by attending courses of lectures on differential and integral calculus in a university. He is prepared for the long course of training but also knows that his final success is assured if he does not give up the effort.

But when it comes to a question of achieving the highest object of human effort which is the culmination of human evolution, people forget all these things based on ordinary common sense and experience. They begin to worry about the difficulty of practising Samadhi and wonder how soon they will be able to rise to the highest states of consciousness which can be brought about by its means. hey imagine that they have merely to make a beginning and all the fruits of Yogic life will be theirs or should be theirs before long. So either they do not make a beginning, or if they do, they become disillusioned and soon give up, thinking either that there is after all nothing much in this much-advertised science of Yoga or that they are incapable of undertaking such a difficult task. So we go on postponing this effort and finding ourselves practically at the same stage life after life. We do not adopt a common-sense attitude towards the problem as we do in the case of a similar problem connected with our worldly pursuits.

The science of Yoga can be mastered like all other sciences by a graduated course of training. We begin with simple things which everyone can do and proceed, step by step, from the simple to the complex problems, from easy practices to the more difficult ones. On account of the different potentialities hidden in different individuals, our progress is regulated not by years of work but by the growth of capacities and changes in our mind and attitudes.

Let us deal first with some of these preliminary practices and disciplines which prepare the aspirant for the more advanced practices which constitute Higher Yoga.

The following Sutra of chapter II gives in a nutshell the general outline of this preliminary or preparatory training with which every aspirant can start at once and lay a sound foundation of a Yogic life systematically and energetically.

“Austerity, self-study and resignation to Ishvara or God constitute preliminary Yoga.” (II-1)

The student will see that the three different types of activity which the sutra prescribes are meant to develop all the three fundamental aspects of human nature, will, intellect and love. Intellectual knowledge lays the foundation of Yogic life by preparing an adequate theoretical background. The development of love or devotion and the transformation and purification of life which this involves adds wisdom to knowledge. And then by the application of spiritual will in controlling and inhibiting the modifications of the mind the Yogi passes from the stage of wisdom to that of Realization, the whole training and self-discipline culminating in Self-Realization and Liberation. The significance of the three elements of this preliminary self-discipline has been explained in detail in the commentary and we need not go into their detailed consideration here. But there are a few general points of interest which may be brought to the notice of the aspirant.

The first point to note is that all these three types of activity constitute a real beginning of the Yogic life and it depends upon the aspirant himself how he utilizes them for a quick transition from the preparatory stage to an advanced stage of progress. If he attacks the problems connected with these activities energetically and earnestly he can in a short time acquire a grip over his lower nature and that concentration of purpose, which will make him fit to take up the more advanced practices of Higher Yoga.

Self-Study

Tapah, Svadhyaya and Ishvara Pranidhana appear to be mysterious practices but there is nothing mysterious about them. Svadhyaya begins with the intensive study of the deeper problems of life so that we may have an adequate theoretical background and may acquire a correct and all-round idea of all the problems which are involved in the practice of Yoga and the methods which are employed in solving these problems. But this study must be carried on by ourselves in such a manner that we can gradually develop the capacity to draw out all knowledge from within ourselves and become independent of external aides in this matter. It should also be at a deeper level and should not consist merely in gathering second-hand information from books etc.

The main purpose in Svadhyaya is to unlock the doors of real knowledge within us and have the capacity to draw upon that knowledge at least to a limited extent by opening up a passage between the lower and the higher mind. I am not referring to the knowledge of realities which is acquired through the higher process of Samadhi. I am referring to ordinary intellectual knowledge which is present in the Ego or Individuality functioning through the Causal body and which can be drawn upon if the lower mind is purified and attuned to the Higher Self.

This knowledge is much superior to ordinary second-hand knowledge we acquire from books, observation, etc., because it comes from a higher source and is free from the ordinary errors, uncertainties and distortions which are a feature of indirect knowledge derived by the concrete mind from external sources. So all devices, methods, practices such as reflection, meditation, japa, etc., which have the effect of opening up the channel between the lower and the higher mind come under Svadhyaya and the beginner should make increasing use of them as his interests and capacities grow.

Austerity

Tapah is generally translated as austerities but this gives a wrong impression about the real and essential nature of this feature of preparatory Yoga. This word is derived from the Sanskrit word tapa which means heating to a high temperature to remove the dross from anything. If impure gold is heated to a high temperature all its impurities are gradually burnt out and removed and only the pure unalloyed metal remains.

This is the essential idea behind tapah and it broadly means disciplining our lower nature with the object of purifying it, removing all the dross of weaknesses, impurities, complexes, distortions, etc. so that our body and mind may become pure, harmonious and obedient to our will and can serve as efficient instruments of the Higher Self. Tapah is thus the transmutation of the lower into the higher nature by a process of self-discipline.

Austerities of various kinds may be used and should be used if this is absolutely necessary but they are not an essential part of the process. Purification and control can be brought about by more intelligent and effective methods than by observing rigid vows and subjecting the bodies to unnecessary discomforts and suffering. Each aspirant must use his own individual methods intelligently.

Self-Surrender

As regards Ishvara-Pranidhana which is translated as self-surrender to God, it is really an aspect of devotion and an effective method of developing devotion. I have dealt in three articles [1] with the problems of developing devotion or love of God and these will give us some idea not only about the goal of the path of Love and the state of devotion, but also the methods which are adopted in developing this side of our nature.

All this knowledge has only now to be put to use seriously and perseveringly to produce results. But it requires practice, sincerity and an indomitable determination to succeed. For devotion does not appear in us easily. We are tested and tried to the utmost limit, and this may throw us into despair again and again. But when it does appear it transforms our life, fills us with joy and exaltation to such an extent that we feel that the sacrifices, efforts and sufferings we have gone through are noting compared to the blessing we have received and the grace of God which has descended upon us.

Preparatory Yoga

So you will see that this sutra of five words has a very wide scope and gives a very comprehensive method of preparing ourselves for the higher stages of Yogic life. It practically covers every aspect of our nature and if the methods which are hinted at in its triple discipline are followed sincerely, carefully and enthusiastically it will not only transform our lower nature and bodies into a fitting instrument of the Higher Self but will open new vistas of achievement and unlock hidden energies and potentialities within us which we hardly suspect existing within us.

If we start practising these things which we have learnt, life will be transformed immediately for us and we would then cease to wonder whether it is possible to practise Samadhi, whether we are capable of developing love to the extent that we may be able to achieve some measure of union with the Object or our devotion. Taking again the example of a student who has the determination to become a great mathematician, it is because he starts doing sums in ordinary arithmetic that he becomes interested in mathematics and ceases to worry about integral and differential calculus, which he will learn later on in due course. Although he keeps the final goal in his mind all the time he does not waste his time and energy in thinking about things which do not concern him for the moment. The work which he is engaged in is so absorbing and interesting that it is enough for him for the time being.

It is creative work of any kind which gives joy to life, and the transformation of our nature by methods of preparatory Yoga is creative work of the highest order, more real and more dynamic than making a statue or painting a picture. These artists are dealing with dead things. The man who is making the image of his Real Self to emerge from within his lower nature is dealing with a living and Real thing. A life problem is being solved. A living picture of what we are to be in the future is being painted. A new statue embodying our future perfection is being chiselled out of the rough marble block of our lower nature. It is this Divine creativity in this work which transforms our life into a song in spite of the troubles and tribulations through which we may be passing in the periphery of our consciousness in the external world.

It is a living process of a bud trying to open into a flower with all the natural joy which is always present in such natural unfolding processes. We are trying to bring the future into the present. We are becoming what we are. We do not know what the statue is going to be like but He who is our Innermost Self knows and we feel His guiding hand as we take up the chisel and start shaping the marble block of our crude nature.

Those who are artists know the joy of painting a picture or writing a poem. They can judge what the joy of bringing out a living Divine image which is hidden potentially within us would be. A picture is a dead thing, a statue is a dead thing, but this living thing, which gradually begins to emerge from within us, is a Divine being of infinite potentialities who becomes more and more a vehicle of Divine love, knowledge and power. The completed image may be still in the future, unseen and unknown, but it is this creative work which is involved in bringing it into existence which imparts the joy and enthusiasm to the work in preparatory Yoga.

And in this work age does not matter, circumstances do not matter, even death does not matter. The work can go on continuously even after death if our mind is set in that direction, for our object or goal is within us and will always remain with us wherever we are. For all these external things belong to the phenomenal world and we have now hitched our wagon to the Eternal Star of our Soul who is hidden within us and guiding us to Itself. This is what preparatory Yoga potentially means and can actually mean to anyone who takes up the work in earnest.

The Philosophy of Yoga

The second chapter of the Yoga-Sutras not only gives us an idea about the nature of preparation which is necessary for taking up the advanced practice of Yoga but also outlines very systematically and logically the philosophy upon which the technique is based.

This philosophy of Yoga is supposed to be derived from the philosophy of Sankhya, one of the six major systems of Hindu philosophy. There is no doubt that it resembles the Sankhyan system of philosophy to a great extent though there are certain fundamental differences which cannot be ignored and which have made many scholars doubt whether there is any real connection between the two.

When two systems of philosophy have come down to us from the hoary past and have existed side by side for thousands of years and there is no definite evidence available of their origin it is very difficult to decide such questions which are of interest only to the academic philosophers.

To the aspirant such questions are not of much importance. What he is interested in is the practical technique which has withstood the test of time and experiment for thousands of years and can be utilized with confidence for gaining his object. The philosophy of Yoga provides and adequate basis for this technique and that is all that matters. The theory on which an experimental science is based is necessary and important for correlating and integrating the different techniques which are involved in a coherent whole, but the truth or validity of the theory does not in any way affect the effectiveness of the techniques which are utilized for practical purposes.

For a long time the laws of electricity and electrical phenomena were utilized for all kind of purposes very effectively although the theory which was prevalent for accounting for those phenomena was very incomplete and unsatisfactory. If the whole theory of electricity is found to be quite untenable now on account of any discoveries that might be made in the future, the whole science based on the application of the laws of electricity and its phenomena in scientific developments and industry will remain quite unaffected as a result of this discovery, because these laws and phenomena are based on experimental facts and not speculation of any kind.

Such is the case with the philosophy of Yoga. Although it is a magnificent and a very reasonable philosophy based on the experiences of Adepts, its validity or otherwise does not affect the technique or the usefulness of Yoga as a science for unveiling the deeper mysteries of life and discovering the Reality within ourselves.

Human Condition

Let us now try to gain a general and clear idea about the philosophy upon which the Yogic technique of Patanjali is based. This philosophy is outlined in the second chapter step by step in 26 sutras from sutra 3 to sutra 28. It is not possible to deal with these sutras in detail and only a broad outline of the ideas underlying these sutras and the links in the chain of reasoning upon which the philosophy is based can be given here.

The philosophy starts with the problem of human miseries, limitations and illusions in which all human beings, with very few exceptions, are involved. The sutra which sums up this patent fact of human life is II-15. It means: “To the people who have developed discrimination all is misery on account of the pains resulting from change, anxiety and tendencies, as also on account of the conflicts between the natural tendencies which a man finds in his nature and his thoughts and desires prevailing in a particular period of time.” The sutra has been translated freely in order to bring out the meaning more clearly. Some people will be inclined to consider this statement as rather sweeping and too pessimistic but it requires careful and deep thought to realize how true it is. All the great Teachers of the world have started from this basic fact of human life and we may, therefore, assume the correctness of the statement made in the sutra.

The next question which arises is: Assuming that there is all-pervading misery in human life, is it possible to avoid or to get rid of this misery? The answer to this question is quite clear, unequivocal and emphatic. It is given in sutra II-16, “The misery which is not yet come can and is to be avoided.” That is the kind of answer that a true philosophy of life should give. What is the use of a philosophy or a religion which points out the miseries and limitations of life and then offers you no real solution, no hope or release from these miseries? And yet, many of our modern philosophies are like that. They raise questions and leave them unanswered, they offer remedies which are mere palliatives or no remedies at all.

Causes of Misery

After asserting that the miseries of life can be avoided or transcended the philosophy proceeds to analyse the cause of the misery. Here is another proof of its thoroughness and effectiveness. If you are suffering from any disease or malady you can tackle it in two ways. Either you can apply palliatives, which will remove the very unpleasant symptomatic features of the disease temporarily and partially, or you can adopt the more effective and sensible course of going to the cause of the malady and dealing with it there. In this way alone is it possible to root out the disease completely and forever.

The philosophy of Yoga adopts the latter course. It goes to the root cause of human suffering and limitations and suggests a remedy which removes the cause of the disease and therefore removes the disease completely and finally. The analysis of the cause of human suffering is given in the theory of kleshas which form a chain of causes and effects which has five links.

These are called Avidya or Primal Ignorance; Asmita or identification of pure Consciousness which is free and Self-sufficient and Self-existent with the paraphernalia through which it manifests when it gets involved in manifestation. The third and fourth links are Raga and Dvesha which mean attractions and repulsions of various kinds which arise as a result of this identification of Consciousness with its vehicles and environment and which forge subjective bonds to bind the individual to his vehicles and environment.

And the last link is the final effect of this chain of causes and effects. It is called Abhinivesha and means instinctive clinging to worldly life and bodily enjoyments and the fear that one might be cut off from all of them by death. So you see that the first cause in Avidya or Ignorance and the last effect is human life lived in limitations and illusions of various kinds. We shall not go into further details.

But there is one point which may be cleared up before we pass on further. Avidya is not the ordinary kind of ignorance or even ignorance as it is used in its general philosophical sense. It is a technical term which means really the lack of awareness of our Real Nature. It is because we have lost the awareness of our true Real nature that we have become involved in manifestation. So Avidya is the instrumental cause of the involution of the Monad in manifestation. Why he gets involved in manifestation or how he gets involved in manifestation are really ultimate questions which are outside the realm of the intellect and we shall perhaps get an answer to these questions only when we regain our awareness of Reality on Liberation. For the time being let us take it as a fact that we are involved and it is necessary and desirable for us to get out of these undesirable conditions and limitations in which we find ourselves.

It is obvious that if lack of awareness of our true nature or Reality is the real cause of our subjective bondage or being involved in manifestation then the only real permanent remedy will be regaining this awareness of Reality or knowledge of our true Real nature. This is the next link in the chain of reasoning upon which the philosophy of Yoga is based. It points out that the final effect in the form of miseries of human life is traceable to the Primal cause in the form of loss of awareness of Reality and therefore the only means of transcending the miseries of life is to regain permanently and completely this awareness of Reality. This is expressed in sutra II-26 as follows: “The practice of uninterrupted awareness of the Real is the means of dispersion of Avidya.” No palliatives, no temporary solutions are offered as is done by most modern philosophies.

The next question naturally is: How to practice this awareness of Reality? The answer is given in II-28 as follows: “From the practice of the component exercises of Yoga, on the destruction of impurity, arises spiritual illumination which develops into awareness of Reality.” And this is followed by sutra 29 which gives the well-known eight components exercises or practices of the Yogic technique.

The Science of Yoga

This is in a nutshell, the philosophy of Yoga. It shows really how the Monad gets involved in manifestation through the loss of his Real nature which leads to his identifying himself with his vehicles and all that is associated with them. This identification leads to his developing all kinds of personal attachments, bonds of attractions and repulsions with people and things in the world. It is these which produce all kinds of experiences which are the source of misery, actual or potential. The philosophy then points out the method of Liberation which naturally is the reversal of the whole process of involution and ends in the Monad regaining the awareness of his Real nature. The Science of Yoga is nothing but the technique by which this can be brought about systematically and scientifically.

The above statement merely lays down the principles which are involved in the involution of the Monad and his release from the undesirable conditions when his inner eyes begin to open and he realizes the true nature of life on the lower planes and the necessity and possibility of getting out of these conditions. The actual method of release and the different techniques which are available for the aspirant is a matter of details which can be learnt from a detailed study of Yoga. The aspirant can make a careful study of these methods and learn to apply this knowledge to his own individual case as best as he can.

The important thing is to make an earnest beginning with a pure motive. When this is done all forces of Nature begin to co-operate and help the aspirant in his effort even though outwardly they may appear to block his way and hinder his efforts. This is merely Nature’s way of testing our earnestness and bringing out our hidden powers and strength. We have to learn to persevere in the face of difficulties and if we are patient we shall find the path opening out before us, and unusual and unexpected opportunities coming to us in different ways.

Where to Begin?

But there is one point which I would like to clear up in this connection. Many of us worry ourselves unnecessarily with the question where I should begin and which path I should follow. With regard to the question “Where should I begin?” the answer is: begin anywhere but begin at once. The path to Reality is not a beaten road which we have to find before we can drive our car on it. It is a pathless path which opens from within ourselveves and which we can enter at any point in time or space which should be “Here and Now”.

Three Paths in One

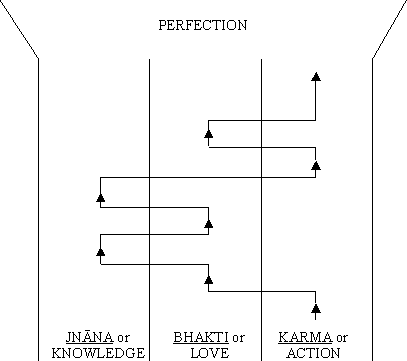

A great deal of misunderstanding exists with regard to this question of following a particular path, one of the three paths of knowledge, devotion and action. Aspirants think that they have to follow one of these paths from beginning to end and so naturally worry unnecessarily as to which path they belong to. The fact is that these different paths are not different roads which we take in trying to reach our goal. They are not really separate and independent roads which lead to a common end, but merely different kinds of techniques which are meant to bring out or develop different aspects of our Divine nature.

Perfection obviously involves a harmonious and all-round unfoldment of our Divine nature. There can be no real ultimate perfection of our Divine nature if there is lop-sidedness, disharmony or deficiency of any kind. So every aspect of our Divine nature has to be unfolded and must be present in its developed form in the final perfection which is attained.

But though the final perfection should contain all these different aspects of our nature in a developed form, these different aspects are best developed by concentration on one particular aspect for a time. The very conditions of human life are such that we can develop one aspect in an intense degree under a particular set of circumstances. This does not mean that we should not try to unfold these different aspects in a balanced and harmonious manner but it is inevitable that the other aspects will have a subordinate place in our life for the time being.

It is this necessity of concentration on a particular aspect at a time that has given rise to the misconception that we are temperamentally suited to tread one particular path and must follow that particular path if we are to succeed in our efforts. As a matter of fact these different conditions of mind and emotions and desires which indicate our fitness for a particular so-called path – Jnana, Bhakti or Karma – are merely phases in our inner development and we should not hesitate to take to a different line if we feel a strong urge to do so. For, it is a question not of treading a particular path but of following a particular technique or rather laying particular emphasis on a particular technique for a time according to the needs of our inner development. Harmonious development does not mean development along all the lines in the same degree. It means that we do not allow any aspect of our nature to lag behind to such an extent that it begins to make us lop-sided, to affect our efficiency and hamper our general progress.

This fact of our passing through different phases of our development and adopting different techniques at different times which makes it appear as if we are treading different paths can be illustrated by the above diagram.

We can start anywhere and after following a particular line in an intensive manner shift to another line in a different incarnation on in the same incarnation. Then we follow this line for some time and then shift again to another line. We are thus enabled to lay emphasis on all aspects by turns and develop them harmoniously. This is Nature’s way of ensuring that we shall not become lop-sided and will ultimately attain an all-round perfection.

• • •

[1 The Theosophist, August, September, October, 1965

This Theosophical Encyclopedia contains all the articles of the printed

This Theosophical Encyclopedia contains all the articles of the printed